"Weighted Voting for Replicated Data"

Problem

Design an algorithm to maintain the replicated data:

- Efficiently update the replicas

- Efficiently communicate with the replicas (i.e., read) to get the latest update

Design Assumptions

- Each replicated object requires a version number

- No version number change during a transaction

Note

The paper is written for transaction. However, the quorum idea universally apply. Thus, I omit some design assumptions related to transactions, which can be checked here.

Algorithm

Weighted Voting

Scene: a file is replicated across a set of replicas. We now need to read/write from this set of replicas to get/write the latest copy of the file.

- Each replica (i.e., server, "Representative" in paper) gets M votes

- Extra read-only copies get 0 votes (i.e., Weak Representatives)

- Each file is assigned K votes

- We require R + W > K when handle each file

- R: the number of replicas we need to read before replying to the clients

- W: the number of replicas we need to write before replying to the clients

- We have at least one overlapping replica between R and W

- Guarantee at least one overlapping replica between R and W

- Guarantee every read will always see the latest write

- To read a file from a set of replicas, we gather R votes from the set of replicas

- Among R reads, we use the version number to detect which is the latest copy of the data and return to the client

- To write a file, we write to the set of replicas that with total votes equal to W (e.g., W=3, Replica 1 has 2 votes, Replica 2 has 0 votes, and Replica 3 has 1 votes; then we need to write to Replica 1 and 3 to meet W requirement)

Quorum-based Reads and Writes

Quorum-based system (e.g., Dynamo) is one special case of Weighted Voting: M = 1; K = N (i.e., the number of replica in the system):

- All reads go to R replicas

- All writes go to W replicas

- We require R + W > N

Tuning & Examples

- R = 1 \(\rightarrow\) reads are efficient, writes are slow (every replica has to be updated)

- W = 1 \(\rightarrow\) writes are efficient, reads are slow (every replica has to be read)

Example:

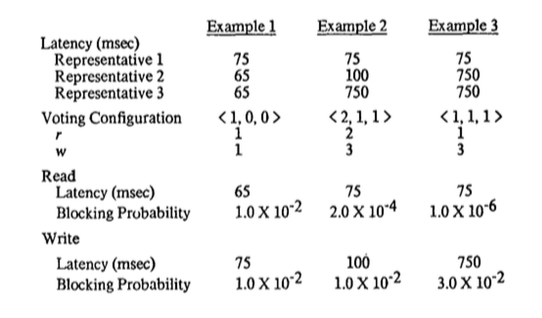

Let's consider Example 1 in the figure above. Representative 1 gets 1 vote and the other two get 0 vote. Replica with 0 votes are weak representatives, which are for read-only (i.e., local cached copy). We have R = 1, W = 1, K = 1 in this example. To read, we have to read Representative 1 because we need 1 vote to satisfy R = 1. At the same time, to write, we need to write to Representative 1 for the same reason. In this example, Representative 1 can be the the server in the clients-server architecture (e.g., NFS) and all the read/write have to go to the server. However, we can also set R = 0, which we can read from the local cached copy directly (Representative 2 & 3 have 0 votes, which satisfy R requirement). But, in this case, weighted-voting algorithm doesn't guarantee that we can get the latest copy of the file.

- Giving each replica (server) one vote: decentralized quorum system with high availability, low performance

- Giving one replica (server) all the votes: centralized system with high performance, low availability

Transactions & Consistency

- Each read or write is an atomic, isolated operation at each copy

- While the read is going on, there is no other writer at that copy (similarly for writes)

- Transactional isolation:

- lock all files the tx wants to read/write; Perform reads/writes; Unlock

- guarantees serializable transactions

- Obtaining the locks has to be done with a total order, otherwise deadlock is possible

- A tx can hold locks for a max time period

- to prevent certain transactions hold locks to long while others are waiting to obtain this lock

Note

On total ordering, we have seen partial ordering in Lamport's logical clock. However, partial ordering allows the existence of concurrent events. To make partial ordering to total ordering, we need to add "comparability", which means for any two events, we can tell the ordering of the events (no cocurrent event allowed). Lamport uses the PID to solve this. In weighted-voting, we enforce total ordering of locks to prevent deadlock. However, we don't enforce total ordering on transactions because operation in transactions can be interleaved and still guarantee the serializability (i.e., serial consistency). We could enforce total ordering on transactions but we cannot achieve the best performance in this case.

- Three locks used: read lock, intention-to-write lock, commit lock

- Unlike write lock, intention-to-write lock allows the read lock because in serial consistency, all of a transaction's writes appear to occur at transaction commit time. Thus, write lock is less ideal because we don't need write lock (which prevents read) at the very beginning of the transaction.

- Writes appear to occur when they are issued, but in fact are buffered until commit time by the stable file system.

- At commit time I-Write locks are converted to Commit locks, and the writing actually takes place.

Note

Very interesting part of the paper on fine-grained locking management to improve concurrency of the system.

Remarks

The paper doesn't have a formal proof on R + W > K guarantees at least one overlapping replica between R and W. I think it would be fun to fill this gap:

Let's suppose there are \(N\) servers and for each server \(i\), we have \(k_i\) with \(k_i > 0\) votes. Then

In words, we read server \(j\) to \(m\) to satisfy R votes requirement and we write server \(h\) to \(t\) to satisfy W votes requirement. Note that \(j\) to \(m\), for example, doesn't enforce that we have to pick servers in sequential order. We can always group the servers we pick for R together and give them the sequential numbering.

Now, let's assume there is no overlapping replica between R and W. That means, \(\{j \dots m\} \cap \{h \dots t\} = \emptyset\). Then we have

From equation \(\eqref{1}\) to equation \(\eqref{2}\), since there is no intersection between two sets of servers, we can pick either \(\{1 \dots h-1\}\) or \(\{t+1 \dots n\}\) to contain \(\{j \dots m\}\) (we happen to choose latter one). In other words, any server in \(\{j \dots m\}\) cannot in \(\{h \dots t\}\) since there is no overlap based on our assumption. From the last equation, we see that the sum of selected votes are smaller than 0, which is contracdiction. We always assign positive votes to each server.