Hash Table

This post summarizes the basic idea about hash table. It is created based on MAW Chapter 5.

Reflection

Motivation

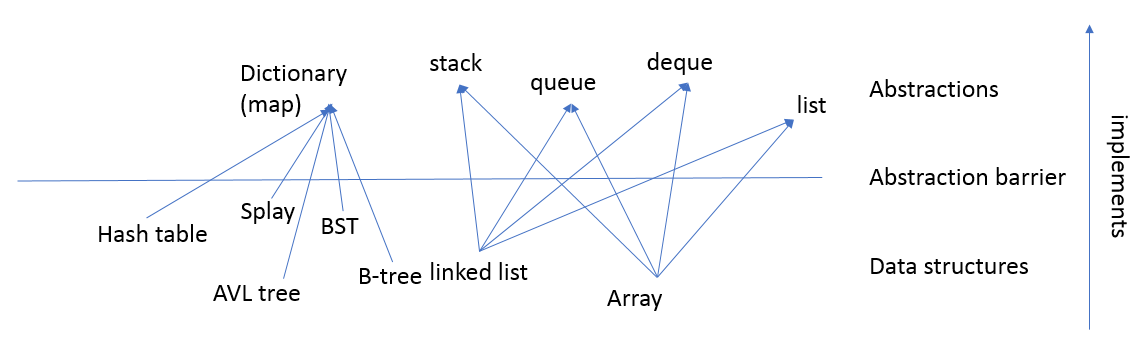

In the previous chapter, we implement the dictionary (map) ADT using tree structure. A typical find or insert operations require \(O(\log N)\) time. However, this is not good enough compared with \(O(1)\) time. This is place where hash tables implementation can shine. Hash tables is a data structure that is designed for \(O(1)\) find, insert, and delete operations. The only downside compared hash tables with tree structure is the ill support for ordering elements.

General Idea

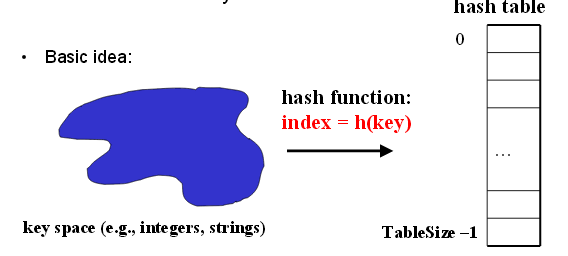

A hash table is an array of some fixed size. Then we use hash function to map each key (i.e. a key is a string with an associated value) into some number in the range 0 to Tablesize-1 and place it in the appropriate cell.

Ideally, two distinct keys get different cells. However, this is not possible because there are a finite number of cells and a virtually infinite supply of keys. Thus the key concern for hash table data structure is how to distribute the keys evenly among the cells. This issue is addressed from two ways: 1) pick a good hash function to avoid collision (i.e. two keys hash to the same value) 2) use a good strategy to redistribute keys when collision happens.

Hash function

Hash function is a mapping from the element key (string or number) to an integer (the hash value). The output of the hash function must always be less than the size of array and should be as evenly distributed as possible. One thing to note here is that the pick of hash function has high dependency on the actual content of the key set.

We list some key points from the chapter here:

- Choose the table size of the hash table to be the prime.

The rationale for this is that real-life data tends to have pattern, and "multiples of 61" are probably less likely than "multiples of 60". In addition, quadratic hashing is an efficient collision strategy to use (compared with linear hashing, double hashing) and it requires the table size to be the prime.

- When we deal with string keys, we may use \(\big(\sum_{i=0}^{k-1} s_i \cdot 256^i \big) \bmod TableSize\) as our function.

Here we use 256 because char data is 1 byte. Other hash function may be adding up the ASCII values ofthe characters in the string. However, this doesn't work well because if string keys are short, it will not hash evenly to all of the hash table (see MAW p.151) and different character combinations hash to same value (i.e. "abc", "bca" all add up to the same value).

The slides listed in the reference section offer some examples on hash function pick if we know the keys beforehand (i.e. if keys \(s\) are the real numbers uniformly distributed over \(0 \leq s < 1\)).

Collision strategy

A collision occurs when two different keys hash to the same value. By the nature of dictionary ADT, we cannot store both data records in the same cell in the array. So, we need to come up a strategy to resolve collision and try our best to make the keys evenly distribute among the table. There are two main strategies discussed in the chapter: separate chaining and open addressing.

Note

Load factor \(\lambda\) defined as the ratio of the number of the elements in the hash table to the table size. This concept appears frequently when we analyze hash table collision resolution strategy.

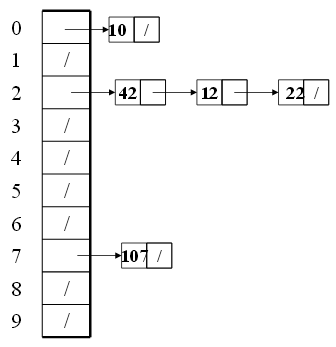

Separate chaining

Note

Sometimes separate chaining is also referred as "open hashing", which means that none of the objects are stored inside the hash table's internal array. For example, objects are stored in lists of buckets for hash table implementng the separate chaining.

Separate chaining is to keep a list (chain or bucket) of all elements that hash to the same value. In other words, each hash table cell holds pointer to linked list of records with same hash value. When collision happens, we insert the hash value of the key to the corresponding linked list of the cell that hash value should be stored. When we want to find an item, we compute the hash value, then do find on linked list.

Here the worst case time happens for find operation, which can take linear time. However, this can happen in the extreme rare case (bad luck or bad hash function). Of course, we can build a balance tree instead of a linked list on each cell to shrink the find time. But, the structure overhead and the compelxity of insert may make this effort not worth it.

The average length of chained list = \(\lambda\). Thus, the average time for accessing an item = \(O(1) + O(\lambda)\). So, we want \(\lambda\) to be smaller than 1 but close to 1 if good hashing function. Thus, the general rule for separate chaining hashing is to make the table size about as large as the number of elements expected (let \(\lambda \approx 1\)).

Note

Actually, separate chaining doesn't restrict us to use the list to chain the objects together. We can use a tree to organize the elements that have the same hash value.

Open addressing

Note

Open addressing is sometimes referred as "closed hashing", which means that every object is stored directly at some index in the hash table's internal array; the objects never live outside of the internal array.

One disadvantage for the separate chaining strategy is that we need to build linked list for each cell, whcih introduces the overhead that can waste space. Another strategy to resolve collision is to try other empty cells. This is called open addressing. In general, open addressing means resolving collisions by trying a sequence of other positions in the table. Trying the next spot is called probing. More formally, cells \(h_0(X), h_1(x), h_2(x), \dots\) are tried in succession until either x is found or we find an empty location (x not present). \(h_i(x) = (Hash(x) + F(i)) \bmod TableSize\), with \(F(0) = 0\). The function \(F\) is the collision resolution strategy.

Various flavors of open addressing differ in which probe sequence they use. This is reflected in \(F\). Three types of resolution function are discussed in the book:

- Linear probing: \(F(i) = i\)

- Quadratic probing: \(F(i) = i^2\)

- Double hashing: \(F(i) = i \cdot Hash_2(x)\)

Generally, the load factor should be below \(\lambda = 0.5\) for open addressing hashing.

Linear probing

With linear probing, we try the cells sequentially (with wraparound) insearch of an empty cell. This strategy has a fundamental problem called primary clustering, which means blocks of occupied cells start forming. Any key that hashes into the cluster will require several attempts to resolve the collision, and then it will add to the cluster. In other words, primary clustering means elements that hash to different cells probe same alternative cells.

Quadratic probing

Quadratic probing is a collision resolution method that eliminates the primary clustering problem of linear probing. But it has its own restriction or problem:

- If quadratic probing is used and the table size is prime, then a new element can always be inserted if the table is at least half empty. However, insertion is not guaranteed if \(\lambda > 0.5\).

- Secondary clustering, which means elements that hash to the same position will probe the same alternative cells.

Double hashing

Double hashing \(F\) says that we apply a second hash function to x and probe at a distance \(hash_2(x), 2hash_2(x), \dots\), and so on.

When \(\lambda\) exceeds certain value, we need to build a bigger hash table of approximately twice the size and be prime. This is called rehashing.

In addition, when hash table cannot be contained in the memory and have to store part of structure on the disk, then the disk I/O becomes the main cost. In this case, we use different hash scheme, which is called extendible hashing. Like B-tree, this structure is widely applied in the database field.

Reference

- MAW Chapter 5

- Washington lecture slides: CSE 332 Lecture 10, CSE 373 Lecture 16

- SO: Meaning of Open hashing and Closed hashing